December 17, 2024

December 17, 2024

The report, known as the “nexus assessment”, explores the interlinkages between climate change, biodiversity, food, water and human health.

It says that focusing on a single element of the nexus at the expense of the others will have negative impacts for both humans and the planet.

At the same time, many of the actions that can be taken to address nature loss will have co-benefits for the climate.

The report also finds that funding for nature is dwarfed by both public and private finance that goes towards nature-harming activities.

However, it says, reforming global financial systems could help address the “funding gap” needed to effectively protect nature.

These conclusions form part of a “summary for policymakers”, a 57-page document that explains the key messages of the report. The full report will be published sometime next year.

IPBES is an independent body that provides scientific advice around biodiversity and biodiversity loss to policymakers, including through the Convention on Biological Diversity. It was modelled after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and functions in much the same way.

Prof Pam McElwee, co-chair of the report and a professor at Rutgers University, told a press briefing that biodiversity, climate, food, water and health should not be treated as “single-issue crises”. She added:

“These are interlinked crises. They are compounding each other. They are making things worse, and the current business as usual approach is not only failing to tackle the drivers of these problems, [but] in some cases, we are wasting money because we’re duplicating policies, when in fact, we could be treating them as issues that need to be dealt with together.”

Here, Carbon Brief explains five key takeaways from the IPBES “nexus” assessment report.

The report explores how the decline of biodiversity in “all regions of the world” has serious consequences for food, water, health and climate change.

It stresses that biodiversity is “essential” to human existence, because it supports water and food supplies, underpins public health and contributes to the stability of the climate.

But over the last 30-50 years, biodiversity has declined by an average of 2-6% each decade across “all of the assessed indicators”, according to the report.

It notes that the ongoing decline has been caused by an intensification of the direct drivers of biodiversity loss: land- and sea-use change, climate change, overexploitation of resources, invasive alien species and pollution.

These trends have, in turn, been caused by “a wide range of indirect drivers”, including economic, demographic, cultural and technological changes, the report argues.

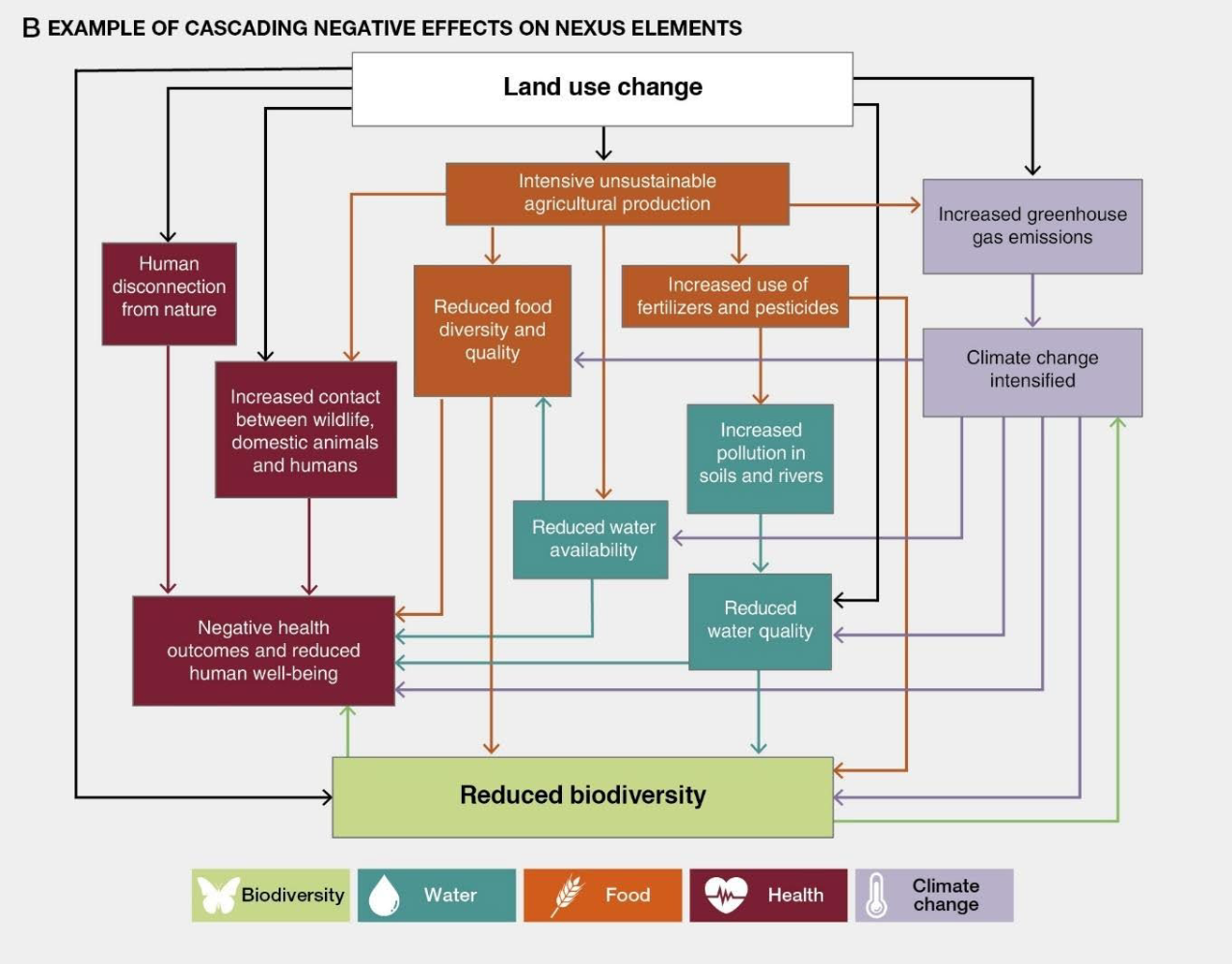

When these “direct” and “indirect” drivers of biodiversity loss interact with each other, they cause “cascading impacts among the nexus elements”, the report warns. In particular, it notes that climate change and biodiversity loss “interact and compound each other to negatively impact ecosystem resilience and all the other nexus elements”.

The document points to “fragmented governance” of biodiversity, water, food, health and climate change as a major obstacle preventing effective action on the issues.

While environmental regulations have been “partially successful”, they are “unlikely to be fully effective without more concerted efforts to address interlinkages among the nexus elements and their direct and indirect drivers”, it warns.

Prof Paula Harrison, co-chair of the report and a scientist at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, says that governance systems need to reflect the interconnections between biodiversity, food, health, water and climate change. She told a press briefing on 16 December:

“Because our current governance systems are often different departments, they are working in silos. They are very fragmented, and they are working and developing policy in isolation – often these links [between climate, health, biodiversity, water and food] are not even acknowledged or ignored.

“What that actually means is that you can just get unintended consequences or trade-offs that emerge because people just weren’t thinking in the holistic way.”

For example, unsustainable agricultural practices introduced to increase food production result in biodiversity loss, unsustainable water usage, reduced food diversity and quality, and increased pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, the report says.

The graphic below provides an illustration of how unsustainable agriculture can impact all five of the nexus elements.

Moreover, the report finds that over the last 50 years, decision makers have prioritised “short-term benefits and financial returns for a small number of people”, while ignoring the negative impacts of their actions on the five nexus elements.

This oversight exacerbates societal inequalities, according to the report, given that communities in developing countries and Indigenous peoples are disproportionately affected by biodiversity loss, water and food insecurity, climate change and health risks.

Overall, it says that “dominant economic systems” are causing “unsustainable and inequitable economic growth”, noting that $7tn a year is invested in activities detrimental to nexus elements.

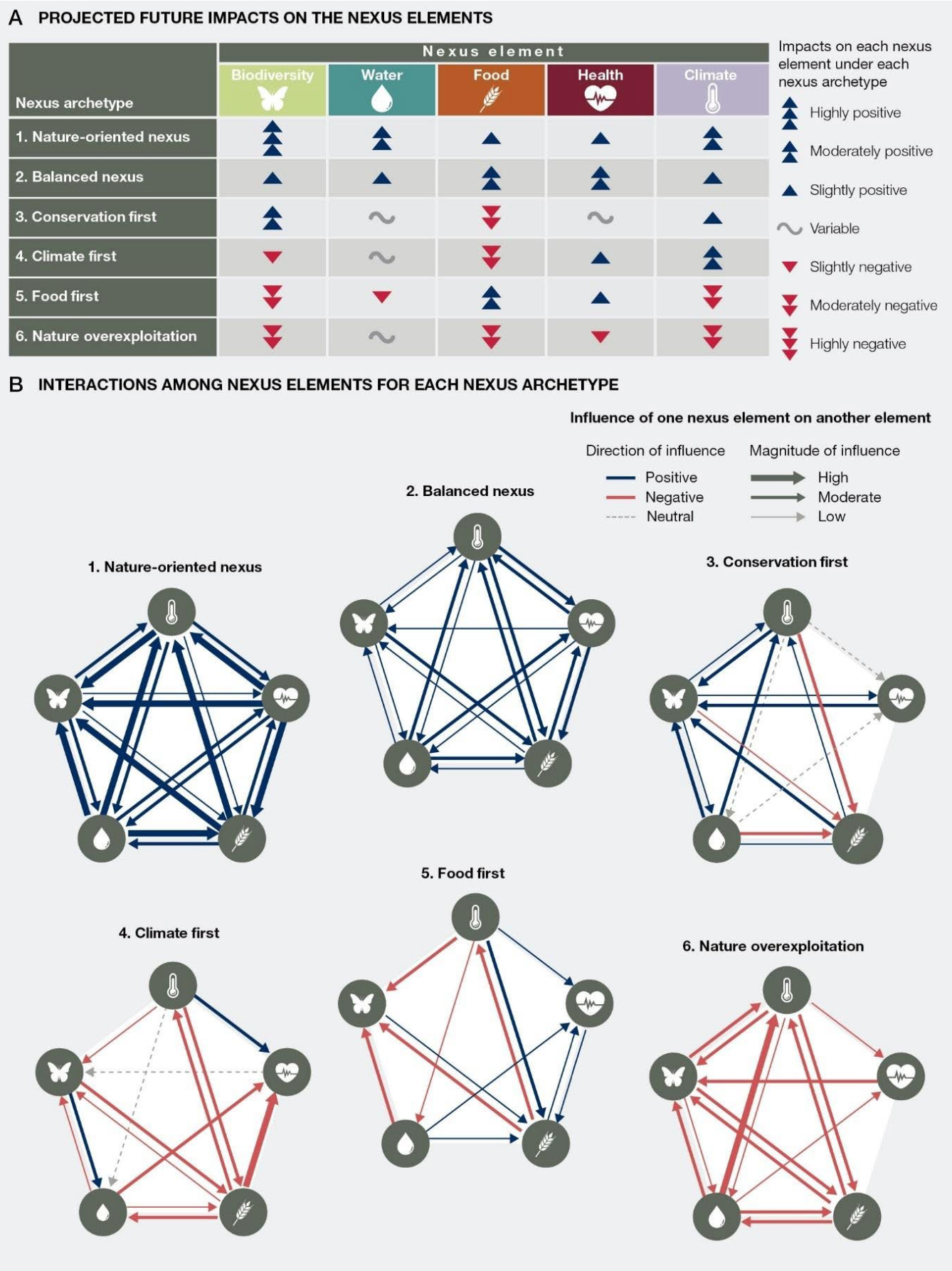

To assess how the five nexus elements – biodiversity, water, food, health and climate – will interact with each other over the 21st century, the authors used 186 scenarios from 52 studies to develop six “nexus scenario archetypes”.

The table below shows the overall projected impact on each nexus element under the different archetypes. The graphic beneath shows how the different nexus elements impact each other under each archetype.

In both graphics, blue arrows show a positive impact, red a negative impact and grey a variable impact. More arrows, or thicker lines, indicate a stronger impact.

The report calls archetypes one and two “sustainability scenarios”.

These are associated with sustainable consumption and production, healthy diets, reduced food waste and lower water use. These archetypes project positive long-term outcomes across all of the nexus elements.

Additionally, the benefits of economic growth are more evenly distributed across different “societal groups”, and multiple actors and knowledge systems – including Indigenous knowledge – are involved in decision-making.

The “nature-oriented nexus” – the first archetype – focuses on increasing protected areas and improving their effectiveness, with a focus on areas with high biodiversity. This takes “deliberate efforts to address existing and emerging injustices and inequality”.

The report finds evidence that “protecting up to 30% of terrestrial, freshwater and marine areas can provide nexus-wide benefits, if these are effectively managed for nature and people”.

The archetype also sees a transformation of global food systems, through changes including increased sustainable agricultural practices, reducing food waste, developing new food sources and promoting healthy, sustainable diets.

Archetype two, called the “balanced nexus”, is characterised by stronger environmental regulation and less reliance on technologies than the nature-oriented nexus. This archetype has a strong focus on restoration and sustainable use of natural resources. It has fewer positive impacts on biodiversity, water and climate and slightly more positive impacts for food and human health, compared to archetype one.

Meanwhile, archetypes three, four and five each prioritise a specific nexus element. These archetypes force “severe trade-offs among the nexus elements” and result in “unsustainable and inequitable economic growth”.

For example, archetype five – “food first” – uses “unsustainable” agricultural processes, which result in higher greenhouse gas emissions, land-use change, water use and nitrate pollution. This scenario sees nutritional health improve, but has negative impacts on biodiversity, water and climate change.

Archetypes five and six are “business-as-usual” scenarios, which represent the continuation of current trends. These are characterised by “intensive…material and energy consumption, increased greenhouse gas emissions, intensive land use and unsustainable exploitation of natural resources”.

The sixth archetype is called “nature overexploitation” and is characterised by negative impacts across all five nexus elements. This archetype sees overconsumption of natural resources, unsustainable energy demand and “weak environmental regulation exacerbated by delayed action”.

The report warns that these business-as-usual scenarios result in “declining outcomes for biodiversity, mainly driven by unsustainable food production and resource extraction as well as climate change”.

The report concludes:

“Maximising all nexus elements simultaneously is unlikely to be possible, but achieving balance across policy goals will likely lead to beneficial outcomes for nature and people.”

The report says it is well established by scientists that shifting to sustainable healthy diets and reducing food waste would “benefit food security and health” and “reduce greenhouse gas emissions”.

This shift could also “free up land, providing in a range of cases co-benefits for nexus elements, such as biodiversity conservation and carbon sinks”, the report says.

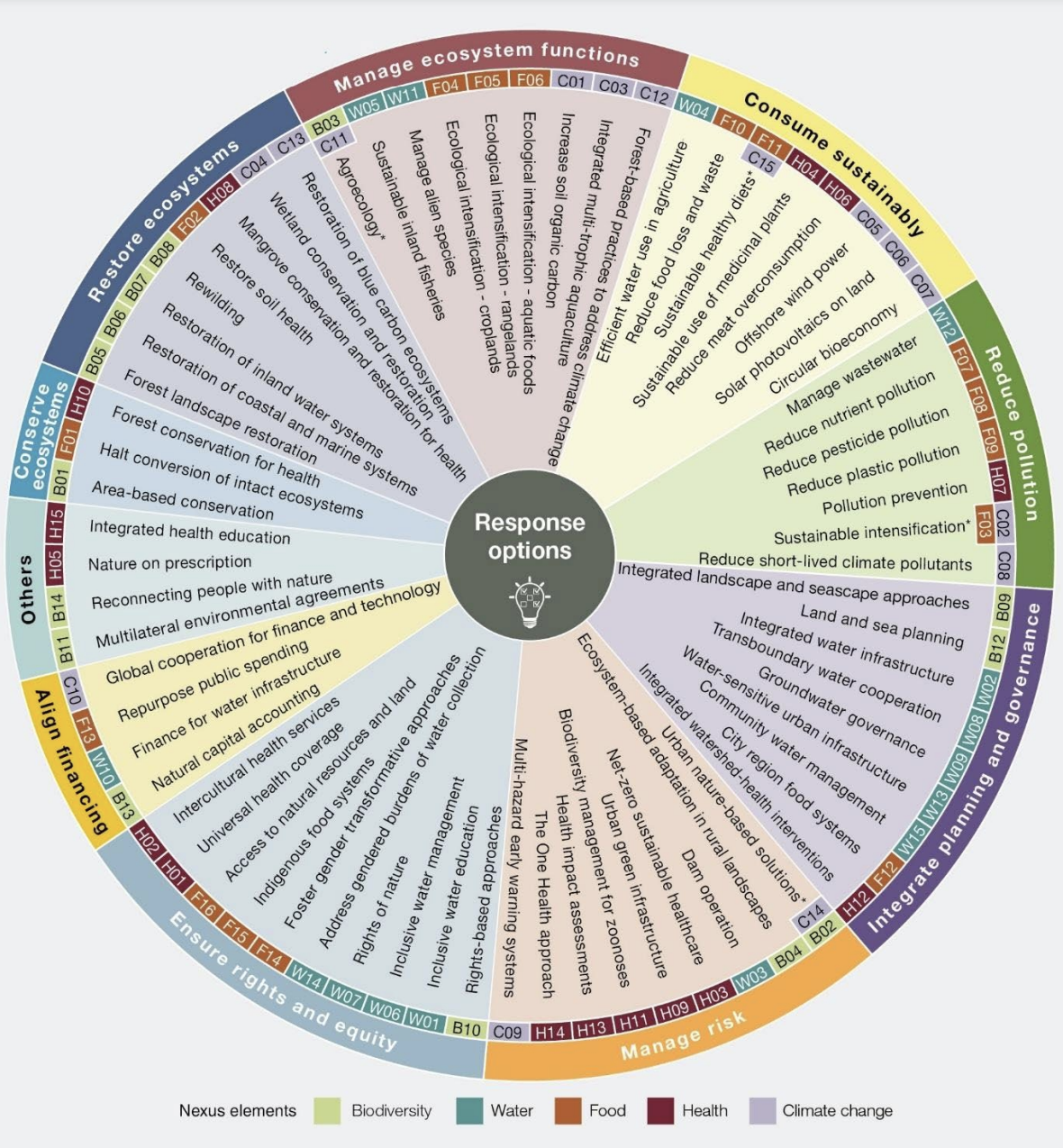

The assessment examines 71 “response options” for tackling at least one element of the nexus between biodiversity, water, food security, health and climate change.

The report says that these responses “are not meant to be an exhaustive list”, but “represent a menu of options that can be applied in different contexts”, adding:

“Some response options may not be appropriate in all countries, and all would be implemented in accordance with national legislation and sovereignty and in accordance with relevant international obligations. Even within countries, effectiveness and acceptability depend critically on political, social and ecological context.”

The graphic below summarises the response options, which are grouped into 10 categories. The coloured tags indicate which element of the nexus the option addresses.

The graphic illustrates how most of the options for addressing food security involve consuming sustainably, managing ecosystem functions and ensuring Indigenous rights and equity.

Measures to consume sustainably in order to boost food security include shifting to sustainable healthy diets and reducing food waste.

The diagram also notes that human health could be improved by reducing meat overconsumption.

The report says it is well established that “behaviour change will be necessary to shift consumption practices”.

It says this can be enabled by the “increasing accessibility and desirability” of sustainable healthy diets. It also says that implementing food-based dietary guidelines to the public, “particularly targeting public school feeding programmes”, can create a “structured demand” for healthy and sustainable food.

This measure could also “increase opportunities for on-farm diversification aimed at increasing supply and consumption of local seasonal foods”, the report says.

The report also says that improving the sustainable use and management of ecosystems is “particularly important for the agricultural sector”.

This is because “the way food is produced, what foods are produced and consumed, where they are produced, and how much food is lost and wasted impact both nature and people”. It says the “ecological intensification” of croplands, rangelands and aquaculture can help to address food security while having benefits for people and nature.

“Ecological intensification” refers to the idea of using natural functions of an ecosystem to produce more food in a sustainable way – for example, by allowing wild insects to pollinate crops.

The report also says “agroecology” could have positive effects for biodiversity and addressing climate change. It says:

“Agroecology represents a shift to production systems where equitable access to land and a blend of scientific and Indigenous and local knowledge guide the sustainable management of biodiversity, crops and other resources.”

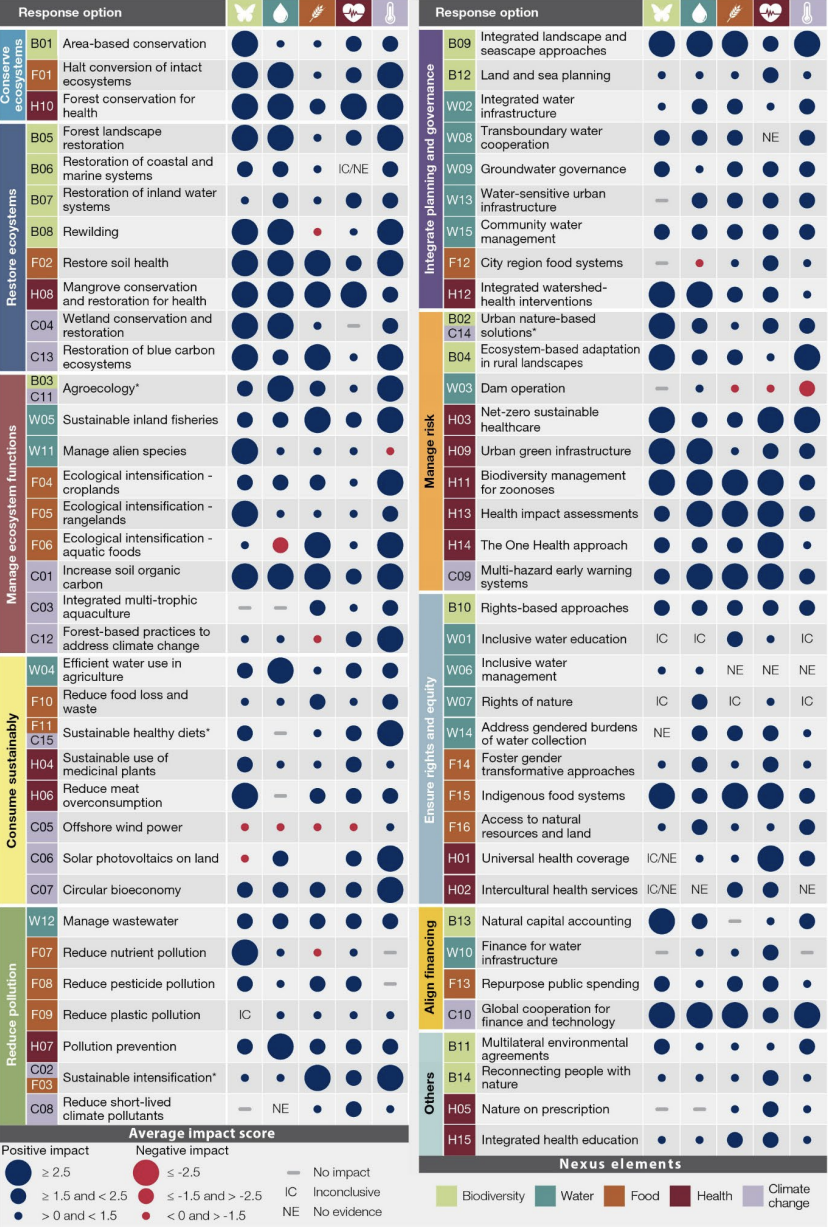

All of the available options for restoring biodiversity examined by the report would come with co-benefits for tackling and adapting to climate change, although the size of this positive impact varies with each technique.

The figure below shows the positive (dark blue) and negative (red) impacts associated with the report’s 71 “response options” for tackling at least one element of the nexus between biodiversity, food security, health and climate change (see previous section for more on these options).

In the figure, positive and negative impacts are shown for biodiversity (butterfly icon), water (droplet), food security (wheat), health (heart) and climate change (thermometer). The size of the circle represents the relative size of the effect.

The figure shows that all of the options for addressing biodiversity loss (B01-14) come with a positive impact on efforts to tackle and adapt to climate change.

Furthermore, the report says, implementing multiple response options together can have a synergistic effect, “enhanc[ing] nexus-wide benefits”. Current approaches, it adds, “have failed to harness the full potential…because they have been designed and implemented in isolation”.

The report says it is well established that addressing nature loss by protecting natural ecosystems from further destruction could come with benefits for all elements of the nexus, adding:

“Conserving or halting conversion of forests and other ecosystems protects human health and wellbeing by combating climate change, reducing the impact of extreme weather events, such as storms, droughts and landslides, increasing water and air quality and reducing disease risk.”

It is also well established that restoring degraded ecosystems can help to tackle climate change “when it targets carbon storage in forests, peatlands, seagrass beds, salt marshes and marine and coastal ecosystems that contribute to carbon sequestration”, the report says.

Restoration is “most effective” when it is inclusive of the knowledge and rights of Indigenous peoples and when it covers large areas, according to the report.

Many of the response options offered in the report support the implementation or achievement of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement.

The report says:

“The capacity to contribute to multiple goals simultaneously is a common and powerful feature of nexus approaches. These response options are therefore a promising mechanism for integrating efforts and accelerating progress towards multiple policy goals and frameworks.”

However, it says, in order to achieve these goals within a nexus framework, “new types of indicators, data and processes may need to be put into place”. It adds that current, siloed methods of governance “have resulted in misaligned, duplicative and inconsistent governance and have failed to address direct and indirect drivers of change”.

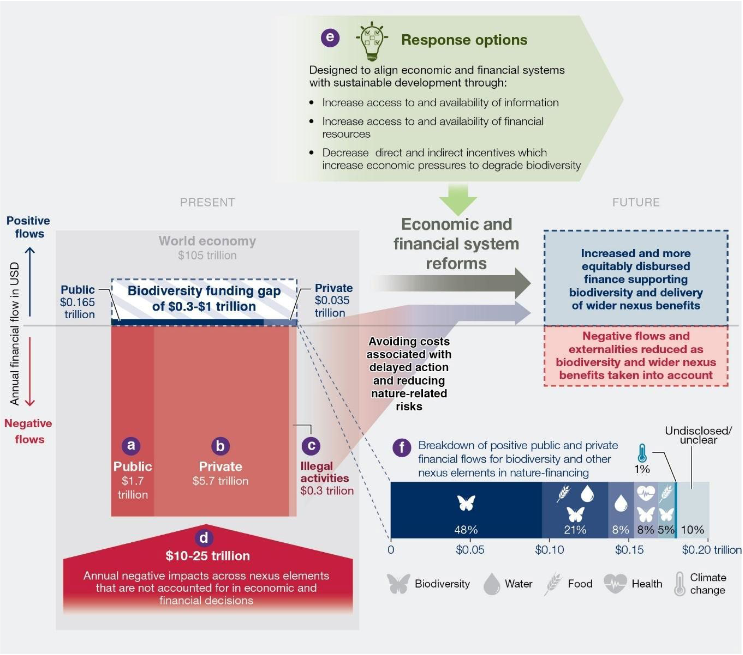

The report identifies the gap in finance needed to meet the needs for biodiversity action as between $300bn and $1tn per year.

Additionally, it says, achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals related to the nexus will require at least another $4tn in investment annually in water, food, health and climate change.

Given those large sums, the report calls for “urgent action” to “address the dominance of a narrow set of interests within economic and financial systems” and increase investment in biodiversity, food and water. It adds that these wider reforms could “amplif[y]” the additional investment made in the nexus.

For example, regulatory reform could make investment in nature more attractive by increasing the costs of biodiversity-harming activities. This is closely linked to target 18 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which calls on countries to “eliminate, phase out or reform incentives” that are harmful to biodiversity.

Target 18 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Source: CBD (2022)

According to the report, there is established but incomplete evidence that the world’s current economic and financial systems are contributing to biodiversity loss and resulting in increased “nature-related risks”, which, it adds, are “mutually reinforcing with risks from climate change”.

These risks are estimated to be “in the trillions of dollars”.

Spending “aimed at improving the status of biodiversity” is estimated at around $200bn per year.

Currently, the world spends 35 times more resources on activities that directly damage biodiversity than it does on preserving nature. This is exacerbated by an additional $300bn spent on illegal activities that harm nature, such as illegal deforestation and wildlife trafficking.

The report identifies three pathways that could help better align global financial flows for biodiversity and the rest of the nexus:

The graphic below shows the current state of funding for the nexus, with biodiversity-harming financial flows shown in red and biodiversity-positive finance in blue. The icons denote the funding that is directed to each element of the nexus: biodiversity, water, food, health and climate change.

The graphic also shows how financial reforms could benefit the nexus by reducing negative finance and increasing biodiversity-supporting finance.

Of the finance that is currently directed towards biodiversity and the other components of the nexus, there are “some existing synergies”, the report suggests. However, more than half of the funding identified in the report goes solely to addressing a single element of the nexus: 48% for biodiversity, 8% for water and 1% for climate change.

Additionally, there is a “clear bias” in the distribution of biodiversity finance, with public funds primarily concentrated in North America, Europe and China, the report says. At the same time, only 5% of global private biodiversity finance is allocated to least-developed countries.

Addressing related concerns, such as the unsustainable debt burden faced by developing countries and striving for just and equitable transitions, can help support financing the nexus as well. The report concludes:

“Collectively, these efforts could reform the relationship between the economy and nature, enhance equity and deliver sustainable development outcomes.”