Currently Featuring

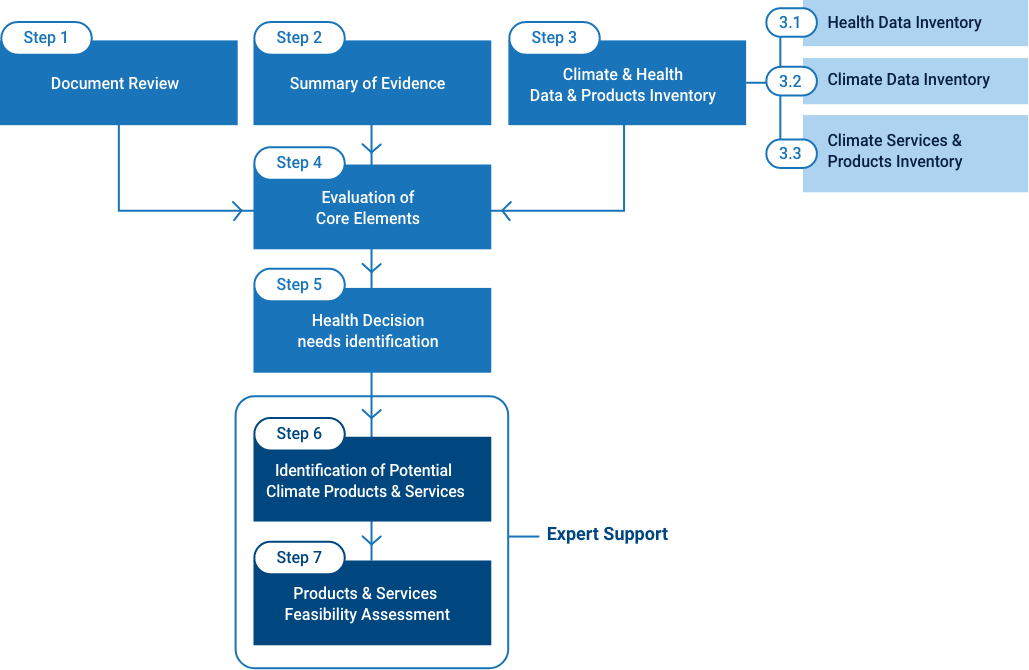

The Readiness Toolkit aims to support countries to identify needs-tailored climate services, and evaluate their feasibility. It does so by guiding countries through understanding their current enabling environment, capacities, and data, evidence and information availability. It is a seven-step additive process to be followed at the national level with support from external experts. Its main six outputs are:

The Readiness toolkit can be used by the national and local health agencies, in coordination with relevant stakeholders such as local epidemiologists, meteorologists, and entomologists, to assess risk from climate hazards and to develop early warning and response strategies.

The assessment includes a combination of seven steps. Steps 1-5 are self-guided, and steps 6-7 are facilitated by external experts.

The process is divided into two parts. The first part provides the first three outputs (a-c) and aims at evaluating the three core elements, the enabling environment, the existing capacities, and the availability of data, information and evidence, for developing climate services that cater to health-decision making needs. It is designed to be carried out at the national level by a national team in collaboration with key stakeholders.

If the current policies, capacities and data/evidence/information are sufficient for the potential development of certain climate services for health, the second part of the process aims at identifying potential climate services and at assessing their feasibility. This part is designed to be conducted by an external expert in consultation with the national team.

Assess the current status of critical and fundamental elements for climate service development.

Before embarking on the Climate Readiness Assessment, a pre-assessment can help you define your aim and the objective. Being clear on the purpose of the Readiness Assessment enables a more effective way of conducting it – focusing on only gathering data and assessing aspects that are relevant. The pre-assessment also identifies the key fundamental elements that need to be in place for climate health service development. Potential gaps need to be addressed before any climate service development can take place.

Review and compile key national policies, strategies, plans, and other key information relevant to climate services development.

Assess current capacities for climate services development and implementation and identify gaps that need to be strengthened.

Identify and provide a description of the available climate and health data, evidence of climate and health linkage, and existing climate services that will serve as the basis for the health-tailored product development.

This includes developing:

Based on the information collected from the previous steps, the national team, together with external experts, should assess the country’s overall state of readiness. Specific core elements should be evaluated to identify gaps that need to be improved for climate services development and implementation for the health sector. Detailed instructions and country-based case studies can be found here.

The supporting experts should evaluate the information compiled in steps 1-3 and, in consultation with the national team, produce a list of climate application areas within the health sector.

The experts should consider current decision-making needs and the needs that might emerge under future climate change impacts – for example the information needs under a potential water-scarce future in some areas of the country.

Produce a list of potential climate services or products that meet country needs.

Each proposed service or product should be described with as much detail as possible, including a description of their data production frequency, geographical coverage, geographical scales, time scales, data and information requirements, technological requirements, etc.

Assess the feasibility of each of the climate products and services identified.

Evaluate the feasibility of each service or product to be developed by reviewing existing or potential climate services or products.

This list is not intended to be exhaustive, and is highly open to expert judgment and criteria for feasibility.

As a bi-product, it will generate a list of gaps in the enabling environment, capacities, and data, evidence and information that will need to be addressed for the services that are rendered unfeasible at this stage.

This exercise is expected to result in a Readiness Report that compiles the information collected through the nine templates and includes a final expert judgment statement on the feasibility of each of the climate service and product proposed.

The feasibility should be graded as:

a) Currently feasible

b) Feasible with a minor increase in capacity

c) Not yet feasible

For services rendered feasible, a list of service requirements needs to be provided (required expertise, data, systems, etc.). For services rendered “feasible provided minor increases in capacity”, in addition to the list of requirements, a list of capacity building needs should be provided. For services rendered unfeasible, a justification should be provided.

For more information and support, please contact: climatehealthoffice@wmo.int

Increasing climate resilience in the health sector demands understanding and using climate information to inform policy and practice decisions. Learn about the WHO framework for building climate resilient health systems, and key steps to identify, envision, develop and apply climate services for health.

Interactive Graph: The WHO operational framework for building climate resilient health systems is comprised of ten components.

Leadership & Governance

In addition to the core functions of ensuring good governance, evidence-informed policy and accountability within the traditional health system itself, the climate resilience approach requires leadership and strategic planning to address the complex and long-term nature of climate change risks. It particularly calls for collaboration to develop a shared vision among diverse stakeholders, and coordinated cross-sectoral planning to ensure that policies are coherent and health promoting, particularly in sectors that have a strong influence on health, such as water and sanitation, nutrition, energy and urban planning.

Health Workforce

Overall, health system functioning relies on a sufficient number of trained and resourceful staff, working within an organizational structure that allows the health system to effectively identify, prevent and manage health risks. Building climate resilience requires additional professional training in linking climate change to health, and an investment in the organizational capacity to work flexibly and effectively in response to other conditions affected by climate change. It also requires raising the awareness of links between climate and health with key audiences (including but not limited to health policy makers, senior staff, the media), and in particular empowering affected communities to take ownership of their own response to new health challenges.

Health Information Systems

This building block focuses particularly on health information systems, including disease surveillance, as well as the research that is required to continue to make health-related progress against persistent and emerging threats. In the context of climate change, there is a specific need for:

Essential Medical Products & Technologies

This traditionally aims to ensure provision of proven, safe and cost-effective healthcare interventions. The challenge of climate change requires a wider perspective, which includes the selection of more climate resilient intervention options both within the healthcare and in health-determining sectors, from renewable energy in health facilities to climate resilient water and sanitation infrastructure. It requires attention to utilization of innovative technologies (such as remote sensing for disease surveillance) and involves reducing the environmental impact of healthcare as a means to long-term sustainability.

Service Delivery

Building and expanding traditional systems of healthcare delivery to enhance climate resilience includes attention to:

Financing

In addition to meeting the existing large demand of financing curative interventions within healthcare systems, there is a need to consider a potential increase in healthcare costs due to climate-sensitive diseases, and develop new models to finance preventive intersectoral approaches. This can include leveraging climate change specific funding streams.

Leadership & Governance

This component refers to the strategic consideration and management of the scope and magnitude of climate related stress and shocks to health systems now and in the future, and their incorporation into strategic health policy, both within the formal health system and in health-determining sectors.

Health Workforce

This component refers to strengthening of technical and professional capacity of health personnel, the organizational capacity of health systems, and their institutional capacity to work with others.

Vulnerability, Capacity & Assessment

This component includes the range of assessments that can be used to generate policy-relevant evidence on the scale and nature of health risks, and the most vulnerable populations, taking into account the local circumstances.

Steps of vulnerability and adaptation (V&A) assessments

Integrated Risk Monitoring & Early Warning

The objective of integrated risk monitoring is to generate a holistic perspective of health risks with real-time information. It uses a set of diverse instruments to bring together information about climatic and environmental conditions, health conditions and response capacity. It is the basis for establishing early warning systems to identify, forecast and communicate high-risk conditions.

Health & Climate Research

Building climate resilience calls for both basic and applied research so as to reduce uncertainty about how local conditions may be affected, gain insight into local solutions and capacities, and build evidence to strengthen decision-making.

Climate Resilient & Sustainable Technologies & Infrastructure

Health system resilience to climate risks builds on provision of essential preventive and curative health products, from vaccines for climate-sensitive diseases to surgical equipment. It can be further enhanced through investment in specific technologies that can reduce vulnerability to climate risks, both within and outside the traditional health sector.

Management Of Environmental Determinants Of Health

Climate change threatens health through environmental determinants, strongly mediated by social conditions. For this reason, some of the most effective actions that can be taken by health systems are in collaboration with other sectors, i.e. through promoting a “Health in all policies” approach.

Climate-Informed Health Programmes

Health programming and operations should consider climate risks and vulnerability and increasingly become climate-resilient through assessment, programming and implementation.

Emergency Preparedness & Management

Outbreaks and health emergencies triggered by climate variability are primary concerns of climate change. Climate-informed preparedness plans, emergency systems, and community-based disaster and emergency management are essential for building climate resilience. Thus, health systems and communities should aim to holistically manage overall public health risks and emphasize preparedness in addition to the usual focus on response capacity. Responses are often late and dominated by ‘emergency’ programming and crisis response, which are resource intensive and not effective in building resilience.

Climate & Health Financing

Effectively protecting health from climate change will incur financial costs for health systems. For example, health systems may need to expend resources to expand the geographic or seasonal range or population coverage of surveillance and control programmes for climate-sensitive infectious diseases, or to retrofit health facilities to withstand more extreme weather events. Additional investment may also be needed in other sectors to achieve health goals, such as implementing climate resilient water safety plans, or enhanced food security forecasting and nutritional screening during droughts.

Climate and weather science is a probabilistic science that is generated, processed and analysed in entirely different ways to health information. Building societal resilience to climate change requires the use of climate and weather knowledge by other fields, and calls not only for translation, but also an understanding of specialized vocabulary and methods, and a substantive dialogue to allow for the synthesis and transfer of knowledge from one field into another.

By definition, climate services are an end-to-end multifaceted process through which a partnership creates a fit-for-purpose information solution. The process of developing a climate service starts with an active discussion between climate information producers and users about specific problems, such as the context, ultimate application, and user specifications. It starts with the question, “What is the climate-sensitive health problem, decision, or policy relevant research question that needs to be addressed, and what is its spatial and temporal dimension?”

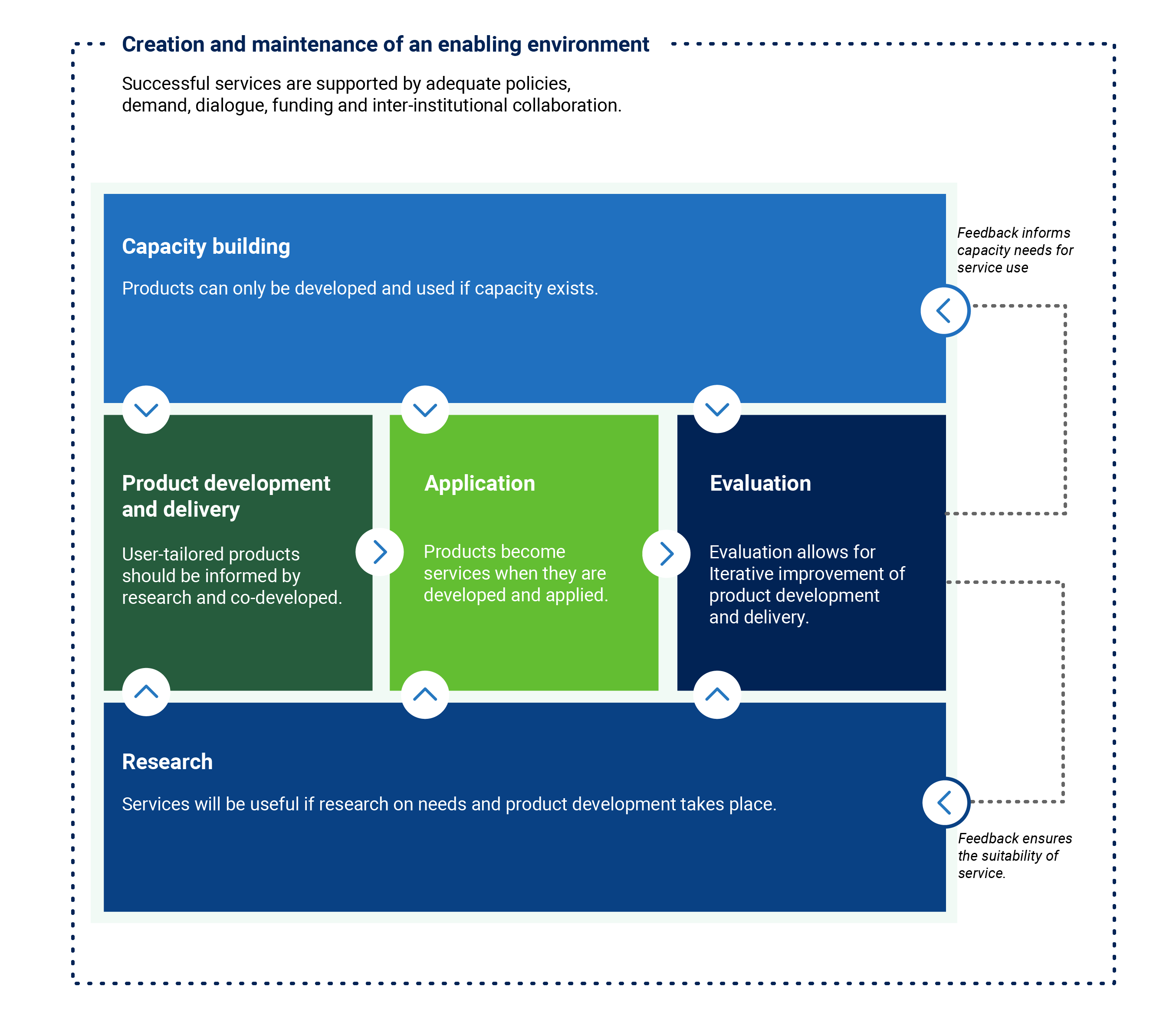

Lessons from the multidisciplinary teams around the world show there is often a common journey taken to identify, envision, develop and apply climate services. Each phase of this journey is important to unlocking insights and unpacking the potential of applied climate knowledge. This common pathway is set out as a six-part framework, illustrated with examples of steps to:

Although this is not a strictly sequential process, the components of enabling environment, capacity, and research set the foundations and readiness levels to adequately advance to product and service development and delivery, application and evaluation.

Additionally, maintaining the enabling environment and strengthening capacities should occur in parallel to activities focused on the design, development, and application of weather and climate services.

Global experiences have shown that although the product development process can be difficult, ensuring that the resulting tools and information are effectively applied and maintained are even greater challenges.

In order to provide a comprehensive health response to climate change, health decision makers need to consider the full range of functions that need to be strengthened to increase climate resilience.

Starting from health sector building blocks, and taking into account existing global and regional mandates, the operational framework for building climate resilient health systems elaborates on 10 components that together provide a comprehensive approach to integrating climate resilience into existing health systems. These can provide the structure for a health adaptation plan, including the allocation of roles and responsibilities, as well as human and financial resources.

In this series of pages, we’ll focus on the steps involved in developing and strengthening health information systems by learning how to identify, envision, develop and apply climate services.

The direct and indirect influences of meteorological and climatic conditions are complex but can result in acute health impacts, as well as slow onset changes in health risk determinants. At one end of a spectrum, extreme weather events can seriously affect people’s mental and physical health and can compromise their access to health care, food, clean water and physical safety, resulting in vulnerability, illness, injury or death.

And at the opposite end, even small or gradual changes in weather and climatic conditions – such as local temperature, humidity or wind direction – can result in significant shifts in people’s exposure to harmful or beneficial conditions, from disease transmission to changing water quality. The growing understanding that changing climate conditions can influence many global health priorities has recently unlocked a strong demand for improved evidence and decision tools that can harness this knowledge for action.

Public health policy and practice is founded upon evidence-based decision making.Professional and ethical standards call upon the field to use rigorous approaches to collect and use the best available information. In the context of climate change, information from the health domain alone is insufficient. It has thus become imperative for public health professionals to take a transdisciplinary approach to problem solving, which includes building partnerships that generate appropriate, integrated and actionable scientific knowledge about the health impacts of climate and weather exposure. Strengthening the climate resilience of the health sector will increasingly call for reliable and robust climate services. Robust and tailored climate products and services can become a powerful part of the public health toolkit that enhance the evidence and information available to detect, monitor, predict, and manage climate related health risks.

Customized tools can be developed to identify and target the most vulnerable areas or populations. Analytical diagnostics can improve available evidence about how, when and where climate can affect human exposure to hazardous or beneficial conditions, who is likely to be affected, and what the magnitude, pattern and duration of the exposure and vulnerability are likely to be. Future climate scenarios can be explored to hypothesize how service delivery may perform under diverse climatic conditions and evaluate which health interventions are most likely to be effective at different times of the year.

At a broad level, health decisions that can benefit from being informed by weather and climate information include:

Climate services for health have been developed to monitor how and where smoke plumes move during forest fires to anticipate when and where populations may be in harm’s way; to map disease transmission risks at high spatial resolution to better target vector control interventions and train traditional healers; to provide real-time and customized information for high-risk populations during heat waves; or to understand changing drought risks and reduce vulnerabilities to rapid and slow-onset impacts of droughts. There are many measurable benefits of climate-informed decisions resulting from applied climate services. Lives can be saved and case burdens reduced. Health systems and communities can become better prepared for extreme weather events. Health intervention can become more cost-effective.

Climate services represent a process of activities that cannot be accomplished by one sector alone. In the case of climate and health, health professionals depend on strong partnerships with the national meteorological services and other partners to access relevant data and capacity to solve health challenges and questions related to weather and climate.

Different levels of collaboration may be called for depending on the activity. Where good quality data, capacity, and knowledge sharing capabilities exist, the health community may rapidly expand their use of climate information without additional cumbersome administrative burdens often associated with multi-sectoral arrangements. For example, the analyses of climate and health relationships that strictly use historic observations of quality controlled meteorological data may call for less joint collaboration, but require data services and data sharing policies that will allow health partners to build the evidence base for identifying further potential climate service needs.

However, when the public health problem requires probabilistic weather or climate forecasts, projections or scenario information, close collaboration and co-production of products becomes particularly important.

Co-production not only expands the available expertise and knowledge that can be harnessed for problem solving, it also helps to make informed judgments about the uncertainty and the probabilistic nature of future weather and climate conditions, which are inherently uncertain. Joint accountability for the generation and use of probabilistic information is fundamental.

Developing tailored climate products and services that can be fully mainstreamed into public health decision-making, policy and operations is a multifaceted collaborative process. It calls for first clearly identifying the problem and information needs; having the capacity to interpret the information provided by climate products; having mechanisms to incorporate this information into decision-making; building communication channels with partners and communities involved in risk management or response; and monitoring mechanisms to evaluate the performance of the products.

The development process for creating usable climate products and services for robust public health decision-making may take months to years, and commonly requires iterative rounds of trial and error, capacity-building, and refinements through active partner engagement and collaboration.

Furthermore, the development process should focus not only on the technical specifications of the climate product, but also on the soft processes that are necessary for building capacity for uptake and use.