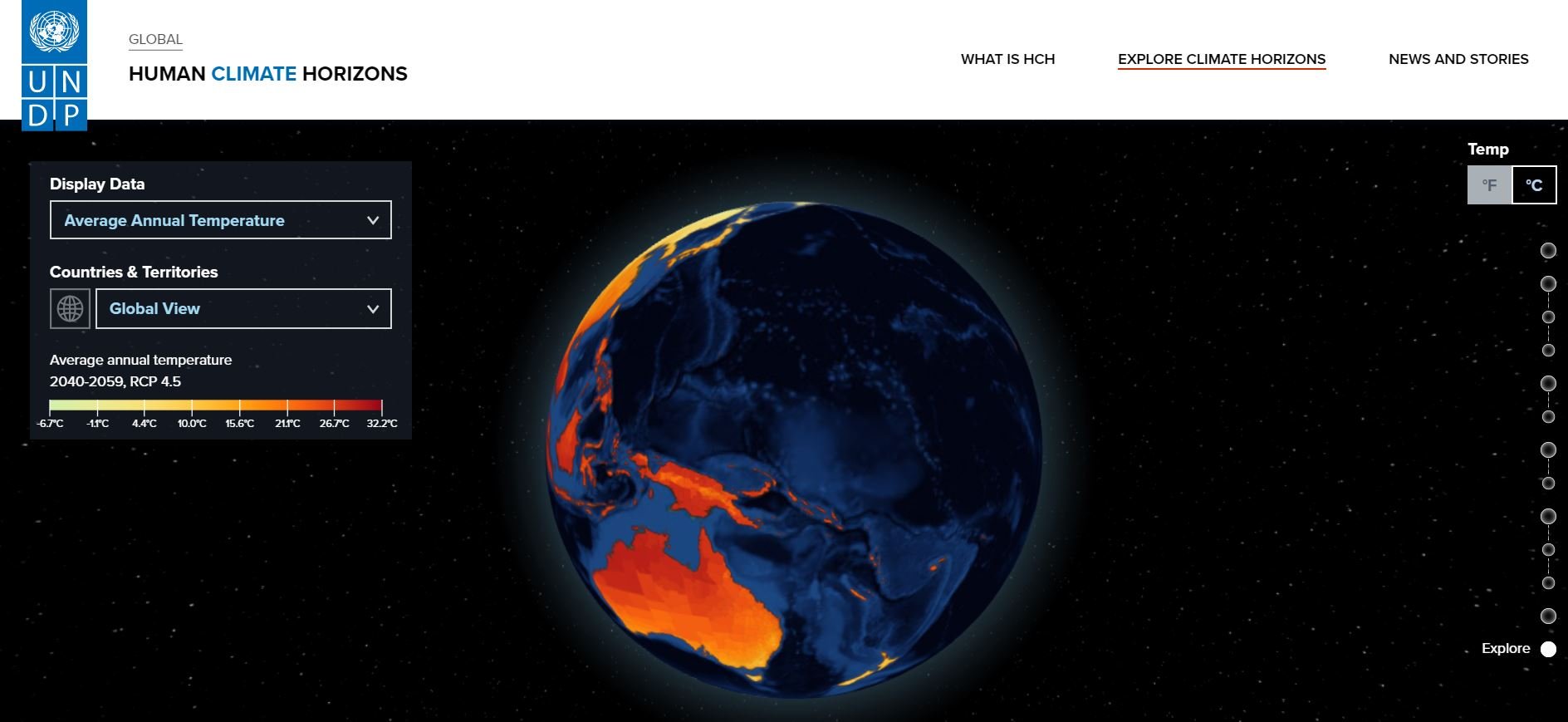

Information and understanding about tropical cyclones (including hurricanes and typhoons) from observations, theory and climate models have improved in the past few years (6–13). Despite this, robust projections for specific ocean basins or for changes in storm tracks are difficult to make. It is anticipated that the total number of tropical cyclones may decrease towards the end of the century. However, it is likely that human-induced warming will make cyclones more intense.

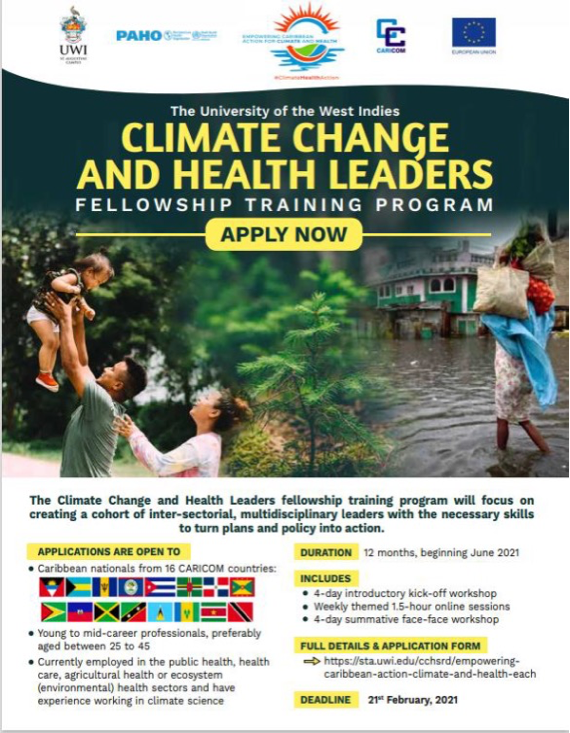

Case Study

Hurricane Dorian, the strongest hurricane in modern Bahamian history, devastated the north-western Bahamas when it struck on 1 September 2019. More than 76 000 residents were affected and 10 000 people evacuated these islands. This created an unprecedented need for mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS). Shortly after Hurricane Dorian passed, staff from the Sandilands Rehabilitation Centre, Public Hospitals Authority, the Bahamas Psychological Association, and a number of NGOs and INGOs were dispatched to the islands and different tent shelters to provide MHPSS. More than 3000 children and 3000 adults received MHPSS either face to face and/or by the telepsychology method. Helplines were also established immediately after the hurricane and more than 500 calls were received, between March 2020 and September 2020, from five islands and also Bahamians in universities outside the country.

It is anticipated that there will be a continuation of MHPSS services, as there may be an increased need given the traumatic experiences, uncertainty, effects of ongoing isolation, and economic situation resulting from both Hurricane Dorian and COVID-19 (case study provided by the Ministry of Health).