Small island developing States (SIDS) face distinct challenges that render them particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change on food and nutrition security including: small, and widely dispersed land masses and populations; large rural populations; fragile natural environments and lack of arable land; high vulnerability to climate change, external economic shocks and natural disasters; high dependence on food imports; dependence on a limited number of economic sectors; and distance from global markets. The majority of SIDS also face a ‘triple-burden’ of malnutrition whereby undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and overweight and obesity exist simultaneously within a population, alongside increasing rates of diet-related NCDs.

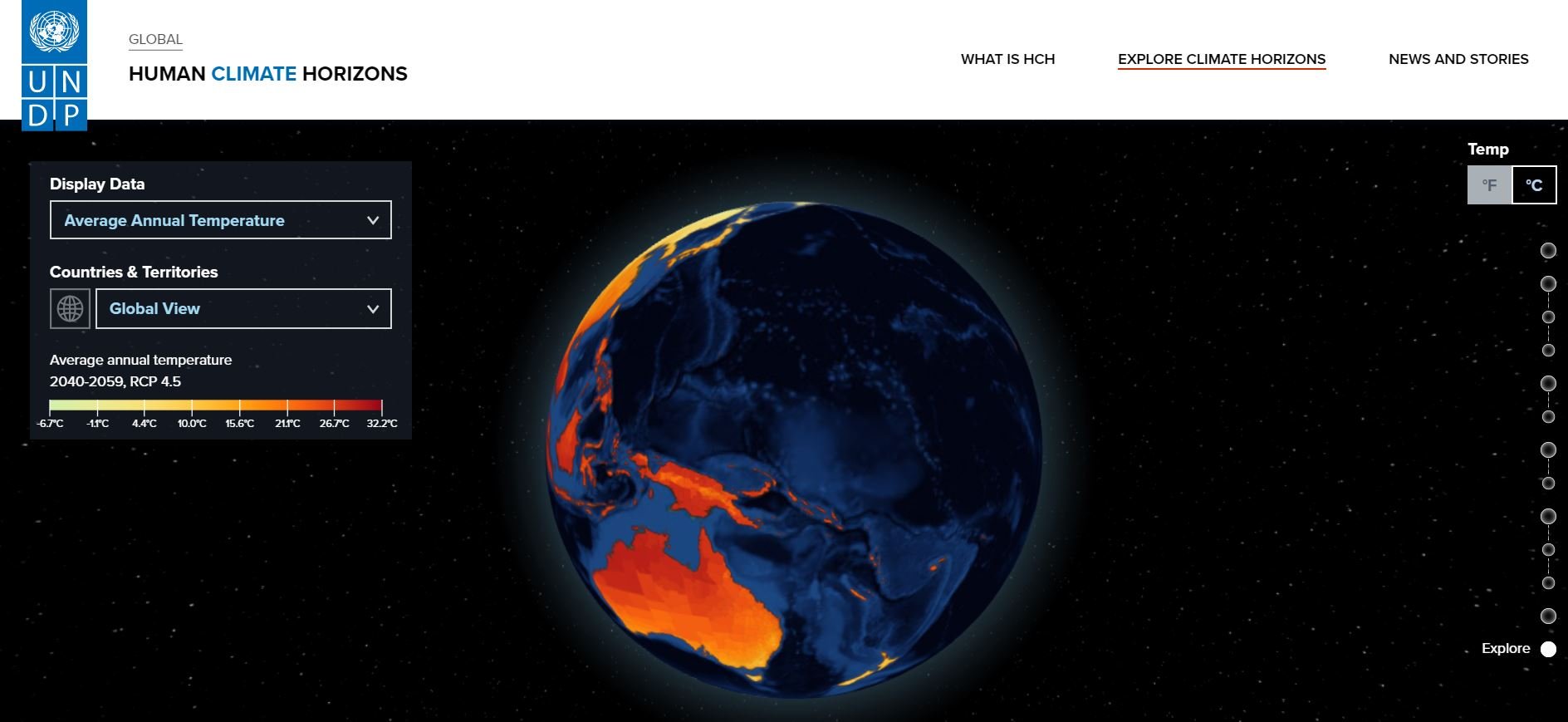

Climate change is likely to exacerbate the triple-burden of malnutrition and the metabolic and lifestyle risk factors for diet-related NCDs. It is expected to reduce short- and long-term food and nutrition security both directly, through its effects on agriculture and fisheries, and indirectly, by contributing to underlying risk factors such as water insecurity, dependency on imported foods, urbanization and migration, and health service disruption. These impacts represent a significant health risk for SIDS, with their particular susceptibility to climate change impacts and already over-burdened health systems; and this risk is distributed unevenly, with some population groups experiencing greater vulnerability.